One of the most important assumptions you need to make when planning for your retirement in today’s low-interest rate environment is the expected length of your lifetime. If you are married, you may also need to make assumptions with respect to how long your spouse may live, how long you both will be alive, and how long just one of you will be alive. We call these assumptions your Lifetime Planning Periods (LPPs). Note that an LPP is not how long you (or your spouse) expect to live (life expectancy), but a period, generally longer than life expectancy, to which you conservatively plan to live to avoid outliving your assets (or, alternatively, to reduce the need to significantly cut back essential spending if you live “too long”). These assumptions can have a significant impact on spending and investment strategies that you may employ in retirement and can affect many of your retirement-related decisions.

In this post, we will:

- Revisit the research of Dr. David Blanchett on selecting planning assumptions for longevity as originally discussed in our post of September 5, 2020,

- Compare Dr. Blanchett’s LPP recommendations for single and joint households with our recommended “default” LPP assumptions developed from the Actuaries Longevity Illustrator (ALI), an online tool developed jointly by the two main actuarial bodies in the U.S. and Canada,

- Discuss the ALI and how we use it in our Actuarial Budget Calculator (ABC) workbooks, and

- Discuss other efforts by the main actuarial bodies to help retirees and near retirees make better financial decisions, and how we believe their guidance can be improved.

We conclude this post by recommending that the main actuarial bodies strongly consider modifying their personal financial educational efforts by advancing basic actuarial principles that can be employed to help people make better financial decisions. We also suggest that the advice they do provide either illustrate how the ALI can be used for retirement planning purposes or reference other sources (like our website) that actually use the ALI in their recommended planning processes (or perhaps do both).

Dr. Blanchett’s Research

When Dr. Blanchett was at Morningstar, he published a report on selecting planning assumptions for longevity entitled, “Estimating the ‘End of’ Retirement.” In this report, he said,

“Through simulations it is determined that adding five years to the life expectancy estimate for a single household, and eight years to the longest life expectancy of either member of a joint household (or to each member if separate end ages are used for spouses), at the assumed retirement age, is a reasonable approach to approximating the retirement period…”

Dr. Blanchett also referred to the Actuaries Longevity Illustrator when he said,

“An example of an online tool, available for free, that provides insight into the probability distribution of survival for both an individual and a couple is the “Longevity Illustrator” tool made available by the American Academy of Actuaries and the Society of Actuaries. The tool incorporates attributes such as age at retirement, years to retirement (that is, improvement), gender, smoker status, and health when estimating mortality rates. The tool also determines the length of retirement, assuming the individual has a 100% probability of surviving to retirement.”

Comparing Dr. Blanchett’s rule of thumb approach with Using the 25% Probability of Survival We Use

In our post of September 5, 2020, we said

“The five year and eight-year amounts noted by Dr. Blanchett are reasonable rules of thumb and are approximately the differences in years between the 50% probabilities (life expectancy) and 25% probabilities of survival from the Actuaries Longevity Illustrator (ALI) that we recommend for the default assumptions in our workbooks.”

As background for the discussion that follows, it should be noted that our default LPP assumptions are based on 25% probabilities of survival for a non-smoker in excellent health from the ALI. However, our Actuarial Budget Calculator workbooks are very flexible, and these default assumptions can be easily overridden to allow the user to select different LPPs.

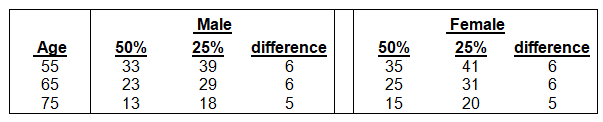

The table below compares LPPs (in years) for males and females of various ages based 50% probabilities of survival with LPPs based on 25% probabilities of survival for non-smokers in excellent health.

50% Probability of Survival (Life Expectancy) vs. 25% Probability of Survival, in years*

The chart above shows that increasing single life expectancies by five or six years as suggested by Dr. Blanchett is roughly equivalent to assuming a 25% probability of survival, at least for non-smokers in excellent health.

Actuaries Longevity Illustrator and How We Use it in our ABC Workbooks

As noted above, the ALI was jointly developed by the American Academy of Actuaries and the Society of Actuaries. The probabilities of survival developed by the ALI are based on mortality tables used by the Social Security Administration in their most recent OASDI Trustees report which are updated annually (and are probably being revised as we write this).

The answer to the first FAQ of the ALI (Why should I consider using something other than life expectancy for financial planning?) indicates that the longevity information developed by the ALI “is crucial towards planning a secure retirement”, but the answer to the second FAQ (How do these charts help me make plans for retirement?) indicates that “this tool is meant only to help you analyze your retiree financial longevity risk and does not consider financial aspects of your retirement planning. Using the ALI is just a starting point to help you consider your options for a secure retirement.”

Our ABC workbooks enable users to move beyond this “starting point” and actually plan for a secure retirement by combining “financial aspects” with the longevity aspects developed in the ALI.

As part of our recommended financial planning process, we recommend building a Floor Portfolio to fund future Essential Expenses. We have previously referred to this strategy as:

- a safety-first strategy,

- a liability driven investment (LDI) strategy,

- a cash-flow matching strategy or

- an actuarial strategy that matches the market value of household non-risky assets with the market value of household Essential spending liabilities.

We accomplish this asset-liability matching by selecting assumptions for real rates of investment return and LPPs that, in combination, are consistent with the theoretical cost of inflation-indexed life annuities. Currently, those assumptions (ABC default assumptions) include a 1% real rate of investment return and LPPs based on 25% probabilities of survival for non-smokers in excellent health. Using the 25% probability of survival is also consistent with generally accepted retirement planning advice to plan to live longer than one’s life expectancy. It is important to note that the same assumptions are used to calculate the present value of expected lifetime Essential Expenses and the present value of low-risk assets (including Social Security, life annuities and pension benefits) to be used to fund the Floor Portfolio.

The two charts below show the cost developed by our ABC workbooks of funding $1 per annum of real dollar lifetime Essential Expenses for a single retiree and for a retired couple.

Estimated Cost of $1 per Annum Real Dollar Lifetime Essential Expenses for a Single Retiree*

Age | Male | Female |

55 | $32.60 | $33.96 |

65 | $25.38 | $26.88 |

75 | $16.59 | $18.26 |

*Based on Default Assumptions

Estimated Cost of $1 per Annum Real Dollar Lifetime Essential Expenses for a Retired Couple*

*Based on Default Assumptions and 33% decrease in Essential Expenses after the first death within the coupleThe costs in the above two charts are based on default assumptions, and the retired couple costs assume that Essential Expenses decrease by 33% after the first death within the couple. Note that this 33% decrease assumption (which we believe is more reasonable) is different from the 0% decrease assumption made by Dr. Blanchett in developing his 8-year rule of thumb, but 0% decreases after the first death within a couple can easily be calculated in our ABC workbooks and results are consistent with Dr. Blanchett’s results. For example, assuming 0% decrease on the first death for the 65/65 age combination above would increase the cost by about $3 to $30.76.

These two charts show that the estimated cost of real dollar future lifetime Essential Expenses for single retirees or retired couples is largely driven by the assumed LPPs.

So, why do we calculate these costs? Since our mission is to help people make better financial decisions in and near retirement, we encourage retirees and their financial advisors to apply these costs to their current estimated Essential Expenses as a starting point to determine whether they have sufficiently funded their Floor Portfolio (with enough assets remaining in their Upside Portfolio to fund their desired future Discretionary Expenses using reasonable assumptions). This, in turn, will provide users with quantitative data points that can be used to assist them in making many retirement-related decisions, including:

- timing of retirement

- timing of Social Security benefit commencement,

- allocation of household assets between risky vs. less-risky investments (including whether or not to take a lump sum distribution from a pension plan if one is available),

- current year spending budgets for Essential and Discretionary Expenses, and

- whether to take a part-time job in retirement.

Advice from Actuarial Organizations on Retirement-Related Decisions

While the two main actuarial organizations in the U.S. and Canada worked jointly to develop the ALI, they have taken somewhat different general approaches when it comes to educating retirees and near-retirees. The American Academy of Actuaries is more policy-focused and generally advocates for lifetime income products and services frequently provided by actuaries. It generally defers to financial advisors when it comes to providing personal financial retirement planning advice. The Society of Actuaries (SOA), however, is not shy about providing such advice to retirees and near retirees. In fact, the SOA actually advertises its 12-part Managing Retirement Decision series in the ALI.

We applaud the Society of Actuaries for its efforts to help retirees and near-retirees make better decisions in retirement. We believe that such efforts are entirely consistent with the profession’s mission of serving the public. We are disappointed, however, that very little of the advice provided by the Society of Actuaries in its Managing Retirement Decision series (or the more limited education information provided by the American Academy of Actuaries) actually incorporates basic actuarial principles (or concepts). These concepts were compiled in 1989 by Charles Trowbridge in his book, “Fundamental Concepts of Actuarial Science”, and include:

- Making assumptions about the future

- Concept of time value of money

- Concept of probabilities

- Mortality

- Use of present values

- Use of generalized individual model that compares assets and liabilities

- Periodic gain/loss adjustment to reflect experience different from assumptions, and

- Conservatism

And despite indicating in the first ALI FAQ that the longevity information developed by the ALI is “crucial towards planning a secure retirement,” none of the twelve SOA Decision Briefs suggests how such longevity information should actually be used to help make the decisions addressed in each separate brief (the ALI is, however, listed as a resource in one of them).

Conclusion

We believe how much one can afford to spend in retirement is a classic actuarial problem that can benefit from a classic actuarial solution developed from basic actuarial principles. We are therefore disappointed that the two main actuarial bodies in the U.S. and Canada fail to endorse the use of such principles in their efforts to help people make better financial decisions. We would encourage these organizations to expand their efforts in this regard by bringing their “A” game, where A stands for Actuarial.

The ALI is an excellent tool developed by the two main actuarial bodies that does a good job illustrating the range of expected lifetimes and the need to plan for a retirement that exceeds one’s life expectancy. We agree with the main actuarial bodies that it represents a “crucial” first step in the retirement planning process, but we believe it needs to be supplemented by financial aspects that are well known to actuaries. We recommend that the main actuarial bodies strongly consider modifying their personal financial educational efforts by advancing basic actuarial principles that can be employed to help people make better financial decisions. We also suggest that the advice they do provide either illustrate how the ALI can be used for retirement planning purposes or reference other sources (like our website) that actually use the ALI in their recommended planning processes (or perhaps do both).